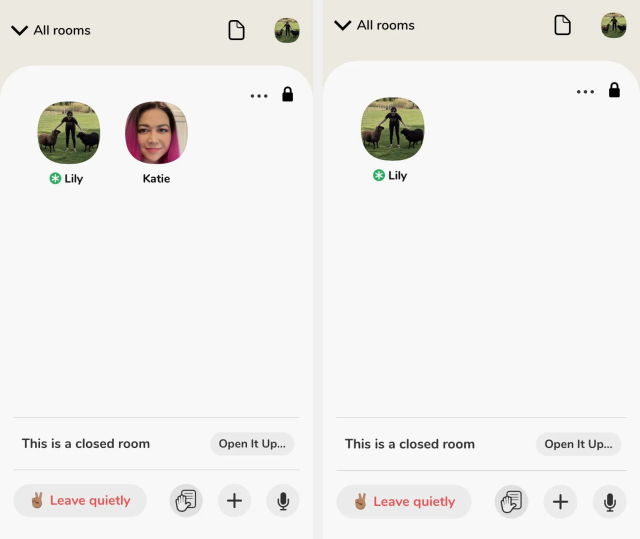

“Basically, I’m going to keep talking to you, but I’m going to disappear,” longtime security researcher Katie Moussouris told me in a private Clubhouse room in February. “We’ll still be talking, but I’ll be gone.” And then her avatar vanished. I was alone, or at least that’s how it seemed. “That’s it,” she said from the digital beyond. “That’s the bug. I am a fucking ghost.”

It’s been more than a year since the audio social network Clubhouse debuted. In that time, its explosive growth has come with a panoply of security, privacy, and abuse issues. That includes a newly disclosed pair of vulnerabilities, discovered by Moussouris and now fixed, that could have allowed an attacker to lurk and listen in a Clubhouse room undetected or verbally disrupt a discussion beyond a moderator’s control.

The vulnerability could also be exploited with virtually no technical knowledge. All you needed was two iPhones that had Clubhouse installed and a Clubhouse account. (Clubhouse is still only available on iOS.) To launch the attack, you would first log in to your Clubhouse account on Phone A and then join or start a room. Then you’d log in to your Clubhouse account on Phone B—which would automatically log you out on Phone A—and join the same room. That’s where the problems started. Phone A would show a login screen but wouldn’t fully log you out. You’d still have a live connection to the room you were in. Once you “left” that same room on Phone B, you would disappear but could maintain your ghost connection on Phone A.

Moussouris also found that a hacker could have launched the attack, or variations on it, using more technical mechanisms. But the fact that it could be done so easily underscores the importance of the flaw. Moussouris calls the eavesdropping attack “Stillergeist” and the interrupting attack “Banshee Bombing.”

Since the vulnerability existed for any room, she argues that the weakness represented a worst-case scenario for Clubhouse as the platform works to deal with privacy issues, harassment, hate speech, and other abuse. Not knowing who’s listening in on a conversation, or having to shut down a room because you can’t stop an invisible person from saying whatever they want, are nightmare situations for an audio chat app.

After Moussouris submitted her findings to the company in early March, she says Clubhouse was not immediately responsive, and it took a few weeks to fully resolve the issue. Ultimately, Clubhouse explained to Moussouris that it patched two bugs related to the finding. One fix made sure any ghost participants were always muted and couldn’t hear a room even if they were hovering in it, essentially trapping them in Clubhouse purgatory. The second bug fix resolved a cache display issue, so users are more fully logged out on an old device if they log in to another. Moussouris says she hasn’t fully validated the fixes herself, but that the explanation makes sense.

“We appreciate the collaboration of researchers like Katie, who helped us identify a few bugs in the user experience and allowed us to swiftly address those to remove any vulnerability before any users were affected,” a Clubhouse spokesperson said in a statement. “We welcome continued collaboration with the security and privacy community as we continue to grow.”

Moussouris waited to publish her research today rather than going live immediately after Clubhouses’s fixes, to honor the full 45-day disclosure window she set for the startup. The company has a bug bounty program through the third-party vendor HackerOne.

Other researchers who have worked with Clubhouse on security disclosures and data requests through the California Consumer Privacy Act say that the company has been slow to respond. Similarly, journalists emailing the main Clubhouse press inbox typically receive an autoreply: “The Clubhouse team is receiving an overwhelming number of media requests. Unfortunately, we are not able to respond to all inquiries.”

Whitney Merrill, a privacy and data protection lawyer and former Federal Trade Commission attorney, says she encountered these growing pains while trying to file a CCPA request with Clubhouse. The law entitles California residents to request their own information from a data company and receive it within 45 days. Even though Merrill isn’t a Clubhouse user, she strongly suspected that the company held some of her data, because it prompts users to share their address books with the app. After weeks of no response, Merrill says she was eventually able to see the data Clubhouse holds about her and request its deletion.

“I don’t think there are the right incentives for startups to care about privacy and security issues, so you end up fighting the exact same battles that were already fought with other organizations 10 years ago,” Merrill says. “And it’s not that no one is learning their lesson, but the incentives to be compliant or to care about these things just aren’t there.”

At least you don’t run the risk of being Banshee Bombed by a deranged Clubhouse ghost anymore.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.