The FBI spent much of Tuesday locked in an online tug-of-war with one of the Internet’s most aggressive ransomware groups after taking control of infrastructure the group has used to generate more than $300 million in illicit payments to date.

Early Tuesday morning, the dark-web site belonging to AlphV, a ransomware group that also goes by the name BlackCat, suddenly started displaying a banner that said it had been seized by the FBI as part of a coordinated law enforcement action. Gone was all the content AlphV had posted to the site previously.

Around the same time, the Justice Department said it had disrupted AlphV’s operations by releasing a software tool that would allow roughly 500 AlphV victims to restore their systems and data. In all, Justice Department officials said, AlphV had extorted roughly $300 million from 1,000 victims.

An affidavit unsealed in a Florida federal court, meanwhile, revealed that the disruption involved FBI agents obtaining 946 private keys used to host victim communication sites. The legal document said the keys were obtained with the help of a confidential human source who had “responded to an advertisement posted to a publicly accessible online forum soliciting applicants for Blackcat affiliate positions.”

“In disrupting the BlackCat ransomware group, the Justice Department has once again hacked the hackers,” Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco said in Tuesday’s announcement. “With a decryption tool provided by the FBI to hundreds of ransomware victims worldwide, businesses and schools were able to reopen, and health care and emergency services were able to come back online. We will continue to prioritize disruptions and place victims at the center of our strategy to dismantle the ecosystem fueling cybercrime.”

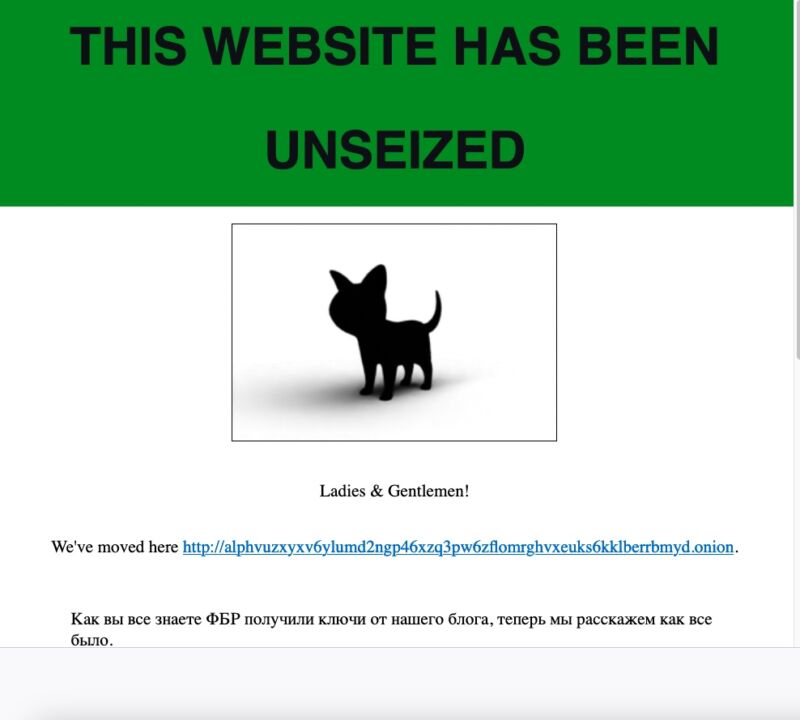

Within hours, the FBI seizure notice displayed on the AlphV dark-web site was gone. In its place was a new notice proclaiming: “This website has been unseized.” The new notice, written by AlphV officials, downplayed the significance of the FBI’s action. While not disputing the decryptor tool worked for 400 victims, AlphV officials said that the disruption would prevent data belonging to another 3,000 victims from being decrypted.

“Now because of them, more than 3,000 companies will never receive their keys.”

As the hours went on, the FBI and AlphV sparred over control of the dark-web site, with each replacing the notices of the other.

One researcher described the ongoing struggle as a “tug of Tor,” a reference to Tor, the network of servers that allows people to anonymously browse and publish websites. Like most ransomware groups, AlphV hosts its sites over Tor. Not only does this arrangement prevent law enforcement investigators from identifying group members, it also hampers investigators from obtaining court orders compelling the web host to turn over control of the site.

The only way to control a Tor address is with possession of a dedicated private encryption key. Once the FBI obtained it, investigators were able to publish Tuesday’s seizure notice to it. Since AlphV also maintained possession of the key, group members were similarly free to post their own content. Since Tor makes it impossible to change the private key corresponding to an address, neither side has been able to lock the other out.

With each side essentially deadlocked, AlphV has resorted to removing some of the restrictions it previously placed on affiliates. Under the common ransomware-as-a-service model, affiliates are the ones who actually hack victims. When successful, the affiliates use the AlphV ransomware and infrastructure to encrypt data and then negotiate and facilitate a payment by Bitcoin or another cryptocurrency.

Up to now, AlphV placed rules on affiliates forbidding them from targeting hospitals and critical infrastructure. Now, those rules no longer apply unless the victim is located in the Commonwealth of Independent States—a list of countries that were once part of the former Soviet Union.

“Because of their actions, we are introducing new rules, or rather, we are removing ALL rules except one, you cannot touch the CIS, you can now block hospitals, nuclear power plants, anything, anywhere,” the AlphV notice said. The notice said that AlphV was also allowing affiliates to retain 90 percent of any ransom payments they get, and that ‘VIP’ affiliates would receive a private program on separate isolated data centers. The move is likely an attempt to stanch the possible defection by affiliates spooked by the FBI’s access to the AlphV infrastructure.

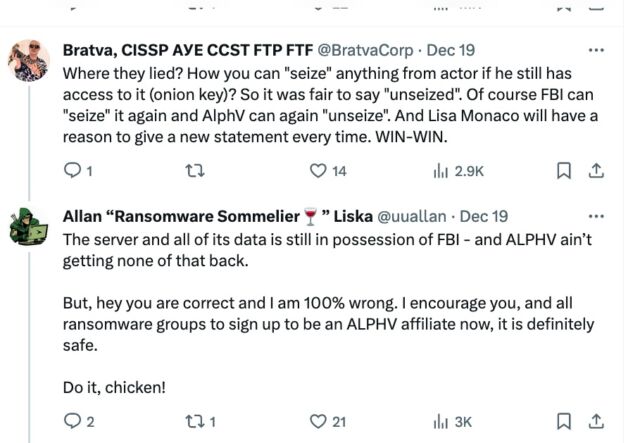

The back and forth has prompted some to say that the disruption failed, since AlphV retains control of its site and continues to possess the data it stole from victims. In a discussion on social media with one such critic, ransomware expert Allan Liska pushed back.

“The server and all of its data is still in possession of FBI—and ALPHV ain’t getting none of that back,” Liska, a threat researcher at security firm Recorded Future, wrote.

“But, hey you are correct and I am 100% wrong. I encourage you, and all ransomware groups to sign up to be an ALPHV affiliate now, it is definitely safe. Do it, Chicken!”