Last August, academic researchers discovered a potent new method for knocking sites offline: a fleet of misconfigured servers more than 100,000 strong that can amplify floods of junk data to once-unthinkable sizes. These attacks, in many cases, could result in an infinite routing loop that causes a self-perpetuating flood of traffic. Now, content-delivery network Akamai says attackers are exploiting the servers to target sites in the banking, travel, gaming, media, and web-hosting industries.

These servers—known as middleboxes—are deployed by nation-states such as China to censor restricted content and by large organizations to block sites pushing porn, gambling, and pirated downloads. The servers fail to follow transmission control protocol specifications that require a three-way handshake—comprising an SYN packet sent by the client, a SYN+ACK response from the server, followed by a confirmation ACK packet from the client—before a connection is established.

This handshake limits the TCP-based app from being abused as amplifiers because the ACK confirmation must come from the gaming company or other target rather than an attacker spoofing the target’s IP address. But given the need to handle asymmetric routing, in which the middlebox can monitor packets delivered from the client but not the final destination that’s being censored or blocked, many such servers drop the requirement by design.

A hidden arsenal

Last August, researchers at the University of Maryland and the University of Colorado at Boulder published research showing that there were hundreds of thousands of middleboxes that had the potential to deliver some of the most crippling distributed denial of service attacks ever seen.

For decades, people have used DDoSes to flood sites with more traffic or computational requests than the sites can handle, denying services to legitimate users. DDoSes are similar to the old prank of directing more calls to the pizza parlor than the parlor has phone lines to handle.

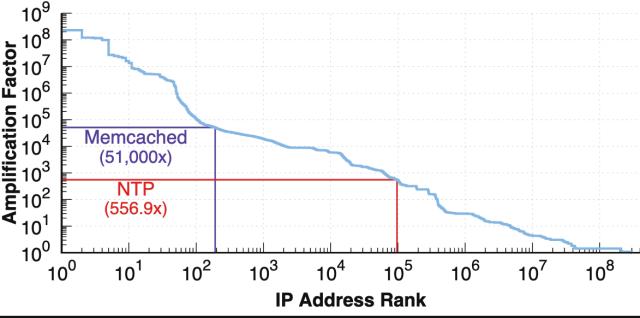

To maximize the damage and conserve resources, DDoSers often increase the firepower of their attacks though amplification vectors. Amplification works by spoofing the target’s IP address and bouncing a relatively small amount of data at a misconfigured server used for resolving domain names, syncing computer clocks, or speeding up database caching. Because the response the servers automatically send are dozens, hundreds, or thousands of times bigger than the request, the response overwhelms the spoofed target.

The researchers said that at least 100,000 of the middleboxes they identified exceeded the amplification factors from DNS servers (about 54x) and Network Time Protocol servers (about 556x). The researchers said that they identified hundreds of servers that amplified traffic at a higher multiplier than misconfigured servers using memcached, a database caching system for speeding up websites that can increase traffic volume by an astounding 51,000x.

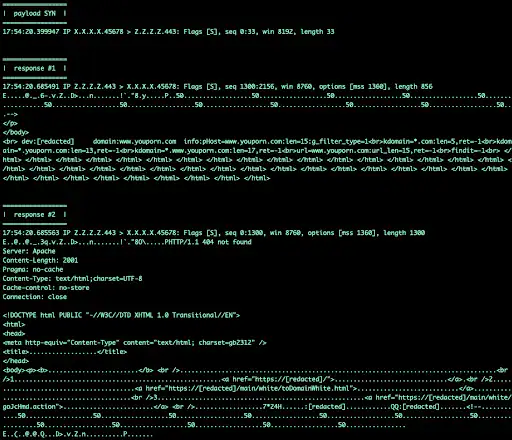

Here’s an overview of how the attacks work:

Day of reckoning

The researchers said at the time that they had no evidence of middlebox DDoS amplification attacks being used actively in the wild but expected it would only be a matter of time until that happened.

On Tuesday, Akamai researchers reported that day has come. Over the past week, the Akamai researchers said, they have detected multiple DDoSes that used middleboxes precisely the way the academic researchers predicted. The attacks peaked at 11Gbps and 1.5 million packets per second.

While small when compared to the biggest DDoSes, both teams of researchers expect the attacks to get larger as DDoSers begin to optimize their attacks and identify more middleboxes that can be abused (the academic researchers didn’t release that data to prevent it from being abused).

Kevin Bock, the lead researcher behind last August’s research paper, said DDoSers had plenty of incentives to reproduce the attacks his team theorized.

“Unfortunately, we weren’t surprised,” he told me upon learning of the active attacks. “We expected that it was only a matter of time until these attacks were being carried out in the wild because they are easy and highly effective. Perhaps worst of all, the attacks are new; as a result, many operators do not yet have defenses in place, which makes it that much more enticing to attackers.”

One of the middleboxes received a SYN packet with a 33-byte payload and responded with a 2,156-byte reply.

That translated to a factor of 65x, but the amplification has the potential to be much greater with more work.

Akamai researchers wrote:

Volumetric TCP attacks previously required an attacker to have access to a lot of machines and a lot of bandwidth, normally an arena reserved for very beefy machines with high-bandwidth connections and source spoofing capabilities or botnets. This is because until now there wasn’t a significant amplification attack for the TCP protocol; a small amount of amplification was possible, but it was considered almost negligible, or at the very least subpar and ineffectual when compared with the UDP alternatives.

If you wanted to marry a SYN flood with a volumetric attack, you would need to push a 1:1 ratio of bandwidth out to the victim, usually in the form of padded SYN packets. With the arrival of middlebox amplification, this long-held understanding of TCP attacks is no longer true. Now an attacker needs as little as 1/75th (in some cases) the amount of bandwidth from a volumetric standpoint, and because of quirks with some middlebox implementations, attackers get a SYN, ACK, or PSH+ACK flood for free.