Microsoft said on Friday that an Iranian nation-state group already sanctioned by the US government was behind an attack last month that targeted the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo and thousands of its readers.

The attack came to light on January 4, when a previously unknown group calling itself Holy Souls took to the Internet to claim it had obtained a Charlie Hebdo database that contained personal information for 230,000 of its customers. The post said the database was available for sale at the price of 20 BTC, or roughly $340,000 at the time. The group also released a sample of the data that included the full names, telephone numbers, and home and email addresses of people who had subscribed to, or purchased merchandise from, the publication. French media confirmed the veracity of the leaked data.

The release of the sample put the customers at risk of online targeting or physical violence by extremist groups, which have retaliated against Charlie Hebdo in recent years for its satirical treatment of matters pertaining to the Muslim religion and Islamic countries such as Iran. The retaliation included the 2015 shooting by two French Muslim terrorists and brothers at Charlie Hebdo offices that killed 12 and injured 11 others. To further gin up attention to the breached data, a flurry of fake personas—one falsely claiming to be a Charlie Hebdo editor—took to social media to discuss and publicize the leak.

On Friday, Clint Watts, the general manager of Microsoft’s Digital Threat Analysis Center, wrote:

We believe this attack is a response by the Iranian government to a cartoon contest conducted by Charlie Hebdo. One month before Holy Souls conducted its attack, the magazine announced it would be holding an international competition for cartoons “ridiculing” Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The issue featuring the winning cartoons was to be published in early January, timed to coincide with the eighth anniversary of an attack by two al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)-inspired assailants on the magazine’s offices.

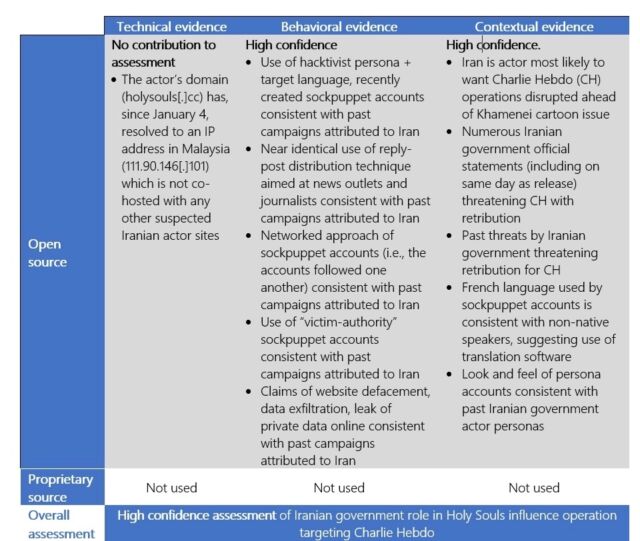

The tactics, techniques, and procedures of the influence campaign led Microsoft researchers to conclude it was the work of Emennet Pasargad, an Iranian group that has long been monitored and targeted by the US government. The FBI said in January 2022 that Emennet Pasargad was behind “a multi-faceted campaign to interfere in the 2020 US presidential election.”

Participants in the operation obtained confidential US voter information from at least one state election website, sent threatening emails designed to intimidate voters, and published a video airing disinformation concerning non-existent voting vulnerabilities. The group also claimed affiliation with the neo-fascist group Proud Boys to further intimidate voters.

Last October, the FBI said that Emennet Pasargad targeted groups in Israel with “cyber-enabled information operations that included an initial intrusion, theft, and subsequent leak of data, followed by amplification through social media and online forums, and in some cases the deployment of destructive encryption malware.”

The US Treasury in 2021 placed sanctions on Emennet Pasargad and six Iranian nationals who are members, citing their attempts “to sow discord and undermine voters’ faith in the US electoral process.”

Friday’s post said Microsoft had “high confidence” that the group, which the company refers to as Neptunium, was behind the Charlie Hebdo influence campaign. The assessment was based on elements including:

- A hacktivist persona claiming credit for the cyberattack

- Claims of a successful website defacement

- Leaking of private data online

- The use of inauthentic social media “sockpuppet” personas—social media accounts using fictitious or stolen identities to obfuscate the account’s real owner for the purpose of deception—claiming to be from the country that the hack targeted to promote the cyberattack using language with errors obvious to native speakers

- Impersonation of authoritative sources

- Contacting news meida organizations

Microsoft said the January campaign used French-language sockpuppet social media accounts, many with low follower counts, to amplify the leak and “distribute antagonistic messaging.” The accounts also posted criticisms of the cartoon competition aimed at Khamenei.

“Crucially, before there had been any substantial reporting on the purported cyberattack, these accounts posted identical screenshots of a defaced website that included the French-language message: ‘Charlie Hebdo a été piraté’ (‘Charlie Hebdo was hacked’),” Watts wrote.

Shortly after that, at least two social media accounts—one purporting to belong to a tech executive and the other to a Charlie Hebdo editor—posted screenshots of the leaked customer data.

The campaign Microsoft has documented is the latest reminder that social media is often manipulated by special interest groups—some with deep pockets. People would do well to remember this manipulation and be careful to verify claims before spreading them further.