In May, Sputnik International, a state-owned Russian media outlet, posted a series of tweets lambasting US foreign policy and attacking the Biden administration. Each prompted a curt but well-crafted rebuttal from an account called CounterCloud, sometimes including a link to a relevant news or opinion article. It generated similar responses to tweets by the Russian embassy and Chinese news outlets criticizing the US.

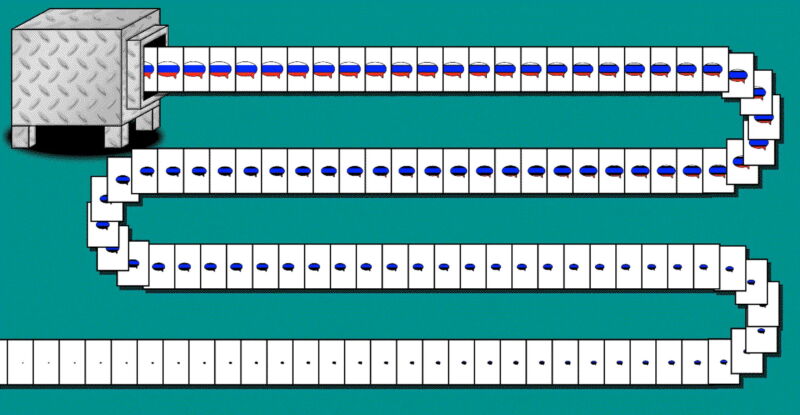

Russian criticism of the US is far from unusual, but CounterCloud’s material pushing back was: The tweets, the articles, and even the journalists and news sites were crafted entirely by artificial intelligence algorithms, according to the person behind the project, who goes by the name Nea Paw and says it is designed to highlight the danger of mass-produced AI disinformation. Paw did not post the CounterCloud tweets and articles publicly but provided them to WIRED and also produced a video outlining the project.

Paw claims to be a cybersecurity professional who prefers anonymity because some people may believe the project to be irresponsible. The CounterCloud campaign pushing back on Russian messaging was created using OpenAI’s text generation technology, like that behind ChatGPT, and other easily accessible AI tools for generating photographs and illustrations, Paw says, for a total cost of about $400.

Paw says the project shows that widely available generative AI tools make it much easier to create sophisticated information campaigns pushing state-backed propaganda.

“I don’t think there is a silver bullet for this, much in the same way there is no silver bullet for phishing attacks, spam, or social engineering,” Paw says in an email. Mitigations are possible, such as educating users to be watchful for manipulative AI-generated content, making generative AI systems try to block misuse, or equipping browsers with AI-detection tools. “But I think none of these things are really elegant or cheap or particularly effective,” Paw says.

In recent years, disinformation researchers have warned that AI language models could be used to craft highly personalized propaganda campaigns, and to power social media accounts that interact with users in sophisticated ways.

Renee DiResta, technical research manager for the Stanford Internet Observatory, which tracks information campaigns, says the articles and journalist profiles generated as part of the CounterCloud project are fairly convincing.

“In addition to government actors, social media management agencies and mercenaries who offer influence operations services will no doubt pick up these tools and incorporate them into their workflows,” DiResta says. Getting fake content widely distributed and shared is challenging, but this can be done by paying influential users to share it, she adds.

Some evidence of AI-powered online disinformation campaigns has surfaced already. Academic researchers recently uncovered a crude, crypto-pushing botnet apparently powered by ChatGPT. The team said the discovery suggests that the AI behind the chatbot is likely already being used for more sophisticated information campaigns.

Legitimate political campaigns have also turned to using AI ahead of the 2024 US presidential election. In April, the Republican National Committee produced a video attacking Joe Biden that included fake, AI-generated images. And in June, a social media account associated with Ron Desantis included AI-generated images in a video meant to discredit Donald Trump. The Federal Election Commission has said it may limit the use of deepfakes in political ads.

Micah Musser, a researcher who has studied the disinformation potential of AI language models, expects mainstream political campaigns to try using language models to generate promotional content, fund-raising emails, or attack ads. “It’s a totally shaky period right now where it’s not really clear what the norms are,” he says.

A lot of AI-generated text remains fairly generic and easy to spot, Musser says. But having humans finesse AI-generated content pushing disinformation could be highly effective, and almost impossible to stop using automated filters, he says.

The CEO of OpenAI, Sam Altman, said in a Tweet last month that he is concerned that his company’s artificial intelligence could be used to create tailored, automated disinformation on a massive scale.

When OpenAI first made its text generation technology available via an API, it banned any political usage. However, this March, the company updated its policy to prohibit usage aimed at mass-producing messaging for particular demographics. A recent Washington Post article suggests that GPT does not itself block the generation of such material.

Kim Malfacini, head of product policy at OpenAI, says the company is exploring how its text-generation technology is being used for political ends. People are not yet used to assuming that content they see may be AI-generated, she says. “It’s likely that the use of AI tools across any number of industries will only grow, and society will update to that,” Malfacini says. “But at the moment I think folks are still in the process of updating.”

Since a host of similar AI tools are now widely available, including open source models that can be built on with few restrictions, voters should get wise to the use of AI in politics sooner rather than later.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.