There are, by some estimates, more smart phones on this planet than human beings to use them. People who have never used a desktop computer use smart phones and other mobile devices every day and have much of their lives tethered to them—maybe more than they should.

As a result, cyber-grifters have shifted their focus from sending emails to gullible personal computer users (pretending to be Nigerian princes in need of banking assistance) and have instead set their sights on the easier target of cell phone users. Criminals are using smartphone apps and text messages to lure vulnerable people into traps—some with purely financial consequences, and some that put the victims in actual physical jeopardy.

I recently outlined some ways to apply a bit of armor to our digital lives, but recent trends in online scams have underscored just how easily smartphones and their apps can be turned against their users. It’s worth reviewing these worst-case scenarios to help others spot and avoid them—and we aren’t just talking about helping older users with this. This stuff affects everyone.

I’ve personally been contacted by a variety of people who’ve been victims of mobile-focused scams and by people who’ve found themselves exposed and targeted via unexpected vulnerabilities created by interactions with mobile apps. For some, these experiences have shattered their sense of privacy and security, and for others, these scams have cost them thousands (or tens of thousands) of dollars. In light of this, it’s worth arming yourself and your family with information and a whole lot of skepticism.

Targeted SMS phishing

The last two years have seen a tremendous uptick in text message phishing scams that target personal data—especially website credentials and credit card data. Sometimes called “smishing,” SMS phishing messages usually carry some call to action that motivates the recipient to click on a link—a link that often leads to a web page that is intended to steal usernames and passwords (or do something worse). These spam text messages are nothing new, but they are becoming increasingly more targeted.

In 2020, the FTC reported that US consumers lost $86 million as a result of scam texts, and the FCC went as far as to issue a warning about COVID-19 text scams. Sure, sure, you’re smart and you would never give up your personal data to a sketchy text message. But what if the text mentioned your name, along with enough correct information to make you just the slightest bit concerned? Like a text message purportedly from your bank, giving your name, asking you to log in to confirm or contest a $500 charge on your credit card at Walmart?

That’s the kind of message I recently received. If I had not read the message carefully or noticed that it had come from a spoofed phone number that was not connected to my bank or failed to remember that I had never consented to any communications with my bank via text messages, I might have clicked.

Instead, I went into my bank’s mobile app and found a notice on the login page that customers were experiencing fraud attempts through text messages. I took the link to my computer and pulled down the page using wget. The link pointed at a Google App Engine page that contained a link in an IFRAME element to a Russian website—one that attempted to emulate the bank’s website login.

SMS scams like these are made easier by the rafts of public data exposure and the aggregation of personal details by marketers. This kind of data is all too often collected in databases that get leaked or hacked. Scammers can target large numbers of customers of a specific brand just by connecting their relationship to a company with their phone numbers. I don’t have good scientific data on the prevalence of targeted “smishing,” but a random sampling of family and friends indicates it’s not just a passing problem: in some cases it constitutes half of the daily SMS messages they receive.

Most of it is the equivalent of pop-up web ads. Some of the targeted SMS messages I’ve seen have purported to be from common services—like Netflix, for example:

Netflix: [Name], please update your membership with us to continue watching. [very sketchy URL]

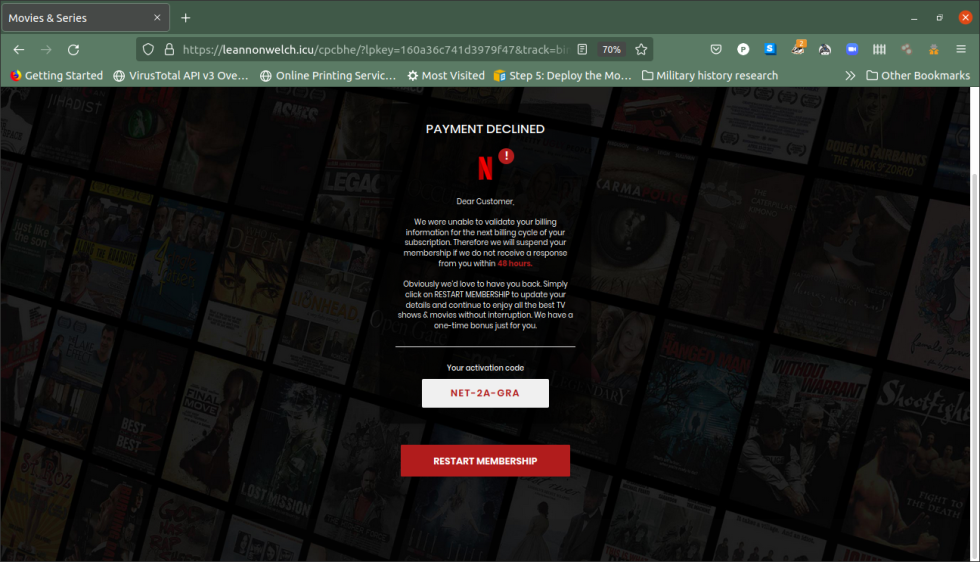

The sketchy link led to a site claiming my last payment had been declined, and I had 48 hours to re-activate my account.

Clicking on that link funnels you into a series of page forwards powered by a “tracker” site configured to filter out suspicious clicks (like ones from PC browsers), sending only mobile browsers to the intended destination—in this case, a Netflix look-alike service that tries to get you to enroll as a member. Your IP address is one of the arguments passed to the final URL in order to keep out undesirable ranges of “customers.”

This is light scamming, to be sure. But the same tracker sites are used by a wide range of scams, including SMS and mobile browser pop-up “fake alert” scams. These types of scams often feature an urgent call to action. Another frequent angle is claiming that the recipient’s IP address “is being tracked due to viruses,” with a link that leads to an app store page—usually some kind of questionable virtual private network app that may in fact do nothing other than collect “in-app payments” through the Apple or Google app stores for a service that doesn’t work. Or the service does work—but not in ways that the device owner would like.

Fleece apps and fake apps

Despite efforts by big companies to check the security of applications before they’re offered for download on app stores, scammer developers regularly manage to slip nasty things into the iOS and Android marketplaces—nasty cheap or “free” apps of limited (or nonexistent) usefulness that deceive users into paying large amounts of money.

Often, these applications are presented as free but feature in-app payments—including subscription fees that automatically kick in after a very short “trial period” that may not be fully transparent to the user. Often referred to as “fleeceware,” apps like this can charge whatever the developer wants on a repeating basis. And they may even continue to generate charges after a user has uninstalled the application.

To be sure that you’re not being charged for apps you’ve removed, you have to go check your list of subscriptions (this works differently on iOS and Google Play)—and remove any that you aren’t using.

Occasionally, malicious applications manage to slip past app store screening. When caught, the developer accounts associated with the apps are usually suspended—and the apps are removed from the stores and (usually) from devices they’ve been installed on. But the developers of these apps often just roll over to another developer account or use other ways to get their apps in front of users.

I tracked a campaign of pop-up ads that drove smart phone users to “security” applications on both app stores, using fake alert pages resembling mobile operating system alerts that warned of virus infections on devices. When the ads detected an iOS device, they ended by opening the page of a VPN application from a developer in Belarus that charged $10 a week for service. The app store listing was replete with (likely fake) 4-star reviews, along with a few from actual customers who discovered they had been scammed.

The app itself worked, sort of—it directed all users’ Internet traffic through a server in Belarus, allowing for man-in-the-middle attacks and the collection of enormous amounts of user data.

Sure, a sophisticated device user would know that these apps are fraudulent and spot them right away, right? Possibly—but how many iOS and Android users have that level of sophistication?