In a development security pros feared, attackers are actively targeting yet another set of critical server vulnerabilities that leave corporations and governments open to serious network intrusions.

The vulnerability this time is in BIG-IP, a line of server appliances sold by Seattle-based F5 Networks. Customers use BIG-IP servers to manage traffic going into and out of large networks. Tasks include load balancing, DDoS mitigation, and web application security.

Last week, F5 disclosed and patched critical BIG-IP vulnerabilities that allow hackers to gain complete control of a server. Despite a severity rating of 9.8 out of 10, the security flaws got overshadowed by a different set of critical vulnerabilities Microsoft disclosed and patched in Exchange server a week earlier. Within a few days of Microsoft’s emergency update, tens of thousands of Exchange servers in the US were compromised.

Day of reckoning

When security researchers weren’t busy attending to the unfolding Exchange mass compromise, many of them warned that it was only a matter of time before the F5 vulnerabilities also came under attack. Now, that day has come.

Researchers at security firm NCC Group on Friday said they’re “seeing full chain exploitation” of CVE-2021-22986, a vulnerability that allows remote attackers with no password or other credentials to execute commands of their choice on vulnerable BIG-IP devices.

“After seeing lots of broken exploits and failed attempts, we are now seeing successful in the wild exploitation of this vulnerability, as of this morning,” Rich Warren, Principal Security Consultant at NCC Group and co-author of the blog wrote.

After seeing lots of broken exploits and failed attempts, we are now seeing successful in the wild exploitation of this vulnerability, as of this morning https://t.co/Sqf55OFkzI

— Rich Warren (@buffaloverflow) March 19, 2021

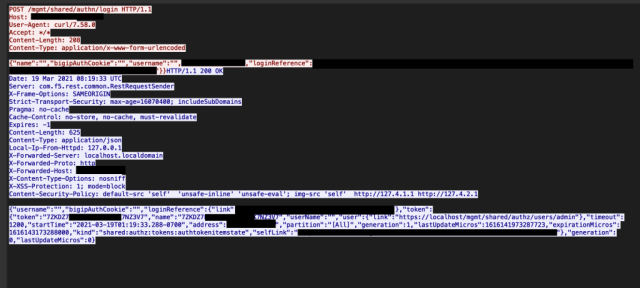

In a blog post NCC Group posted a screenshot showing exploit code that could successfully steal an authenticated session token, which is a type of browser cookie that allows administrators to use a web-based programming interface to remotely control BIG-IP hardware.

“The attackers are hitting multiple honeypots in different regions, suggesting that there is no specific targeting,” Warren wrote in an email. “It is more likely that they are ‘spraying’ attempts across the internet, in the hope that they can exploit the vulnerability before organizations have a chance to patch it.”

He said that earlier attempts used incomplete exploits that were derived from the limited information that was available publicly.

Security firm Palo Alto Networks, meanwhile, said that CVE-2021-22986 was being targeted by a devices infected with a variant of the open-source Mirai malware. The tweet said the variant was “attempting to exploit” the vulnerability, but it wasn’t clear if the attempts were successful.

Other researchers reported Internet-wide scans designed to locate BIG-IP servers that are vulnerable.

Opportunistic mass scanning activity detected from the following hosts checking for F5 iControl REST endpoints vulnerable to remote command execution (CVE-2021-22986).

112.97.56.78 (🇨🇳)

13.70.46.69 (🇭🇰)

115.236.5.58 (🇨🇳)Vendor advisory: https://t.co/MsZmXEtcTn #threatintel

— Bad Packets (@bad_packets) March 19, 2021

CVE-2021-22986 is only one of several critical BIG-IP vulnerabilities F5 disclosed and patched last week. The severity In part is because the vulnerabilities require limited skill to exploit. But more importantly, once attackers have control of a BIG-IP server, they are more or less inside the security perimeter of the network using it. That means attackers can quickly access other sensitive parts of the network.

As if admins didn’t already have enough to attend to, patching vulnerable BIG-IP servers and looking for exploits should be a top priority. NCC Group provided indicators of compromise in the link above, and Palo Alto Networks has IOCs here.

Update: After this post went live, F5 issued a statement. It read: “We are aware of attacks targeting recent vulnerabilities published by F5. As with all critical vulnerabilities, we advise customers update their systems as soon as possible.”

Meanwhile, NCC Group’s Rich Warren responded to questions I sent earlier. Here’s a partial Q&A:

What does “seeing full chain exploitation” mean? What was NCC Group seeing before, and how does “full chain exploitation” change it?

What we mean is that, previously we were seeing attackers attempting to abuse the SSRF vulnerability in a way which could not work, because an important part of the exploit was not public knowledge, therefore the exploits would fail. Now, attackers have figured out the full details needed to use the SSRF to bypass authentication and obtain authentication tokens. These authentication tokens can then be used to execute commands remotely. So far, we have seen the attackers a) obtain an authentication token, and b) execute commands to dump credentials. We haven’t seen any web-shells being dropped like we did with CVE-2020-5902, yet.

Where, precisely, are you seeing the exploit attempts? Is it in a honeypot, on production servers, somewhere else?

The attackers are hitting multiple honeypots in different regions, suggesting that there is no specific targeting. It is more likely that they are “spraying” attempts across the internet, in the hope that they can exploit the vulnerability before organizations have a chance to patch it. Earlier attempts we saw against our honeypot infrastructure showed that attackers were using incomplete exploits based on limited information that was available in the public domain. This shows that attackers are obviously keen to exploit the vulnerability – even if some of them don’t have the requisite knowledge to engineer their own attack code.

Do you know if the exploits are succeeding in compromising production servers? If yes, what are attackers doing post exploitation?

At the moment we can’t comment on whether the same attackers have been successful against other people’s servers. With regards to post-exploitation activities, we have only seen credential dumping so far.

I’m reading that multiple threat groups are exploiting the vulnerability. Do you know this to be true? If so, how many different threat actors are there?

We’ve not stated that there are multiple attackers. In fact, while we’ve seen multiple successful exploitation attempts from different IPs, all attempts have contained some specific hallmarks which are consistent with the other attempts, suggesting it’s likely the same underlying exploit.