With the name Smarter, you might expect a network-connected kitchen appliance maker to be, well, smarter than companies selling conventional appliances. But in the case of the Smarter’s Internet-of-things coffee maker, you’d be wrong.

Security problems with Smarter products first came to light in 2015, when researchers at London-based security firm Pen Test partners found that they could recover a Wi-Fi encryption key used in the first version of the Smarter iKettle. The same researchers found that version 2 of the iKettle and the then-current version of the Smarter coffee maker had additional problems, including no firmware signing and no trusted enclave inside the ESP8266, the chipset that formed the brains of the devices. The result: the researchers showed a hacker could probably replace the factory firmware with a malicious one. The researcher EvilSocket also performed a complete reverse engineering of the device protocol, allowing remote control of the device.

Two years ago, Smarter released the iKettle version 3 and the Coffee Maker version 2, said Ken Munro, a researcher who worked for Pen Test Partners at the time. The updated products used a new chipset that fixed the problems. He said that Smarter never issued a CVE vulnerability designation, and it didn’t publicly warn customers not to use the old one. Data from the Wigle network search engine shows the older coffee makers are still in use.

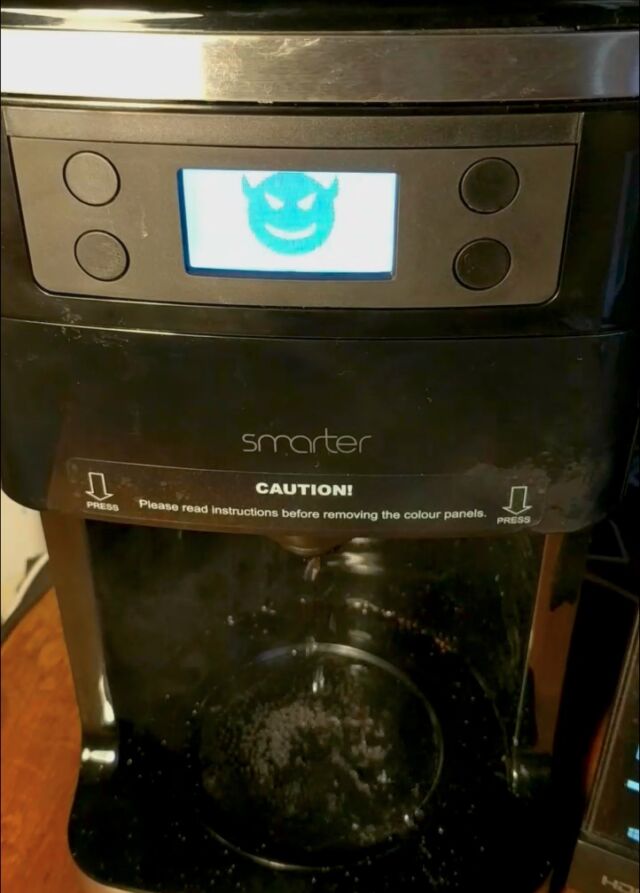

As a thought experiment, Martin Hron, a researcher at security company Avast, reverse engineered one of the older coffee makers to see what kinds of hacks he could do with it. After just a week of effort, the unqualified answer was: quite a lot. Specifically, he could trigger the coffee maker to turn on the burner, dispense water, spin the bean grinder, and display a ransom message, all while beeping repeatedly. Oh, and by the way, the only way to stop the chaos was to unplug the power cord. Like this:

“It’s possible,” Hron said in an interview. “It was done to point out that this did happen and could happen to other IoT devices. This is a good example of an out-of-the-box problem. You don’t have to configure anything. Usually, the vendors don’t think about this.”

In a statement delivered six days after this post went live, Smarter officials wrote:

Smarter is committed to ensuring its smart kitchen range has the highest levels of security safeguards at its core, and all connected products sold since 2017 are certified to the UL 2900-2-2 Standard for Software Cybersecurity for Network-Connectable Devices.

A very limited number of first-generation units had been sold in 2016 and although updates are no longer supported for these models, we do review any legacy claims on a per customer basis in order to provide continued customer care.

What do you mean “out-of-the-box”?

When Hron first plugged in his Smarter coffee maker, he discovered that it immediately acted as a Wi-Fi access point that used an unsecured connection to communicate with a smartphone app. The app, in turn, is used to configure the device and, should the user choose, connect it to a home Wi-Fi network. With no encryption, the researcher had no problem learning how the phone controlled the coffee maker and, since there was no authentication either, how a rogue phone app might do the same thing.

That capability still left Hron with only a small menu of commands, none of them especially harmful. So he then examined the mechanism the coffee maker used to receive firmware updates. It turned out they were received from the phone with—you guessed it—no encryption, no authentication, and no code signing.

These glaring omissions created just the opportunity Hron needed. Since the latest firmware version was stored inside the Android app, he could pull it onto a computer and reverse engineer it using IDA, a software analyzer, debugger, and disassembler that’s one of a reverse engineer’s best friends. Almost immediately, he found human-readable strings.

“From this, we could deduce there is no encryption, and the firmware is probably a ‘plaintext’ image that is uploaded directly into the FLASH memory of the coffee maker,” he wrote in this detailed blog outlining the hack.

Taking the insides out

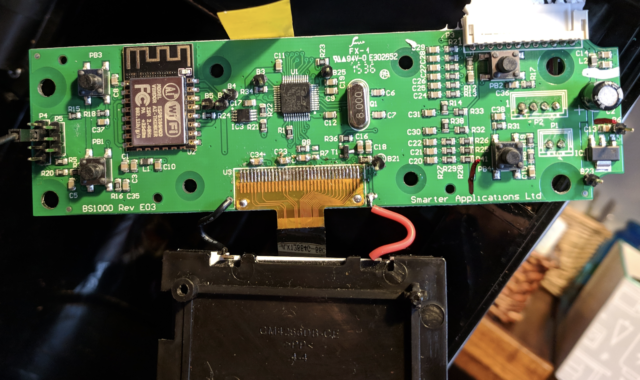

To actually disassemble the firmware—that is, to transform the binary code into the underlying assembly language that communicates with the hardware, Hron had to know what CPU the coffee maker used. That required him to take apart the device internals, find the circuit board, and identify the chips. The two images below show what he found:

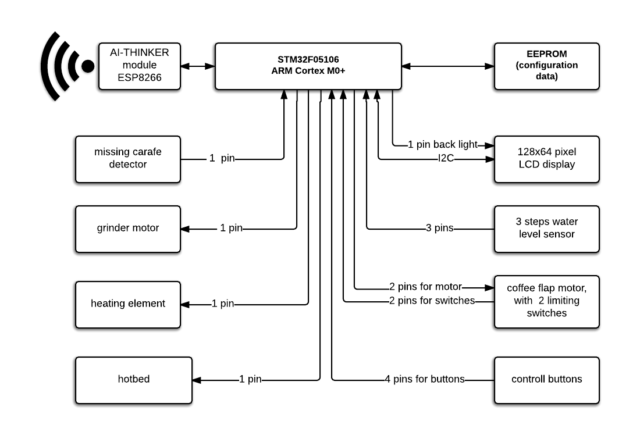

With the ability to disassemble the firmware, the pieces started to come together. Hron was able to reverse the most important functions, including the ones that check if a carafe is on the burner, cause the device to beep, and—most importantly—install an update. Below is a block diagram of the coffee maker’s main components:

Hron eventually acquired enough information to write a python script that mimicked the update process. Using a slightly modified version of the firmware, he discovered it worked. This was his “hello world” of sorts:

Freak out any user

The next step was to create modified firmware that did something less innocuous.

“Originally, we wanted to prove the fact that this device could mine cryptocurrency,” Hron wrote. “Considering the CPU and architecture, it is certainly doable, but at a speed of 8MHz, it doesn’t make any sense as the produced value of such a miner would be negligible.”

So the researcher settled on something else—a machine that would exact a ransom if the owner wanted it to stop spectacularly malfunctioning the way shown in the video. With the benefit of some unused memory space in the silicon, Hron added lines of code that caused all the commotion.

“We thought this would be enough to freak any user out and make it a very stressful experience. The only thing the user can do at that point is unplug the coffee maker from the power socket.”

Once the working update script and modified firmware is written and loaded onto an Android phone (iOS would be much harder, if not prohibitively so because of its closed nature), there are several ways to carry out the attack. The easiest is to find a vulnerable coffee maker within Wi-Fi range. In the event the device hasn’t been configured to connect to a Wi-Fi network, this is as simple as looking for the SSID that’s broadcast by the coffee maker.

Beachhead

Once the device connects to a home network, this ad hoc SSID required to configure the coffee maker and initiate any updates is no longer available. The most straightforward way to work around this limitation would be if the attacker knew a coffee maker was in use on a given network. The attacker would then send the network a deauthorization packet that would cause the coffee maker to disconnect. As soon as that happens, the device will begin broadcasting the ad hoc SSID again, leaving the attacker free to update the device with malicious firmware.

A more opportunistic variation of this vector would be to send a deauthorization packet to every SSID within Wi-Fi range and wait to see if any ad hoc broadcasts appear (SSIDs are always “Smarter Coffee:xx,” where xx is the same as the lowest byte of the device’s MAC address).

The limitation of this attack, it will be obvious to many, is that it works only when the attacker can locate a vulnerable coffee maker and is within Wi-Fi range of it. Hron said a way around this is to hack a Wi-Fi router and use that as a beachhead to attack the coffee maker. This attack can be done remotely, but if an attacker has already compromised the router, the network owner has worse things to worry about than a malfunctioning coffee maker.

In any event, Hron said the ransom attack is just the beginning of what an attacker could do. With more work, he believes, an attacker could program a coffee maker—and possibly other appliances made by Smarter—to attack the router, computers, or other devices connected to the same network. And the attacker could probably do it with no overt sign anything was amiss.

Putting it in perspective

Because of the limitations, this hack isn’t something that represents a real or immediate threat, although for some people (myself included), it’s enough to steer me away from Smarter products, at least as long as current models (the one Hron used is older) don’t use encryption, authentication, or code signing. Company representatives didn’t immediately respond to messages asking.

Rather, as noted at the top of this post, the hack is a thought experiment designed to explore what’s possible in a world where coffee machines, refrigerators, and all other manner of home devices all connect to the Internet. One of the interesting things about the coffee machine hacked here is that it’s no longer eligible to receive firmware updates, so there’s nothing owners can do to fix the weaknesses Hron found.

Hron also raises this important point:

Additionally, this case also demonstrates one of the most concerning issues with modern IoT devices: “The lifespan of a typical fridge is 17 years, how long do you think vendors will support software for its smart functionality?” Sure, you can still use it even if it’s not getting updates anymore, but with the pace of IoT explosion and bad attitude to support, we are creating an army of abandoned vulnerable devices that can be misused for nefarious purposes such as network breaches, data leaks, ransomware attack and DDoS.

There’s also the problem of knowing what to do about the IoT explosion. Assuming you get an IoT gadget at all, it’s tempting to think that the, uh, smarter move is to simply not connect the device to the Internet at all and allow it to operate as a normal, non-networked appliance.

But in the case of the coffee maker here, that would actually make you more vulnerable, since it would just broadcast the ad hoc SSID and, in so doing, save a hacker a few steps. Short of using an old-fashioned coffee maker, the better path would be to connect the device to a virtual LAN, which nowadays usually involves using a separate SSID that’s partitioned and isolated in a computer network at the data link layer (OSI layer 2).

Hron’s write-up linked above provides more than 4,000 words of rich details, many of which are too technical to be captured here. It should be required reading for anyone building IoT devices.

Story updated to add second and third paragraphs explaining earlier work Hron’s hack builds upon.

Listing image by Avast