Law enforcement agencies including the FBI and the UK’s National Crime Agency have dealt a crippling blow to LockBit, one of the world’s most prolific cybercrime gangs, whose victims include Royal Mail and Boeing.

The 11 international agencies behind “Operation Cronos” said on Tuesday that the ransomware group—many of whose members are based in Russia—had been “locked out” of its own systems. Several of the group’s key members have been arrested, indicted, or identified and its core technology seized, including hacking tools and its “dark web” homepage.

Graeme Biggar, NCA director-general, said law enforcement officers had “successfully infiltrated and fundamentally disrupted LockBit.”

“LockBit has caused enormous harm and cost. No longer,” Biggar told a media conference in London, flanked by officials from the FBI, US Department of Justice, and Europol. “As of today, LockBit is effectively redundant. LockBit has been locked out.”

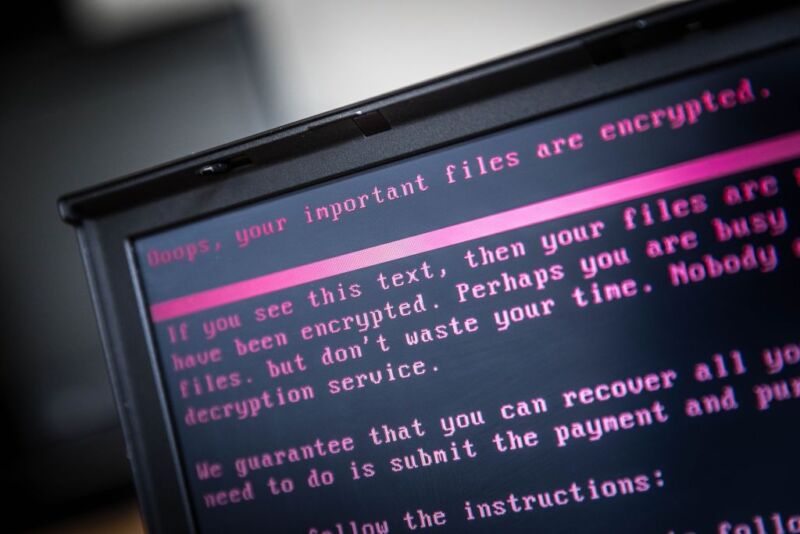

Over the past four years, LockBit has been involved in thousands of ransomware attacks on victims around the world, from high-profile corporate targets to hospitals and schools.

The hacking group’s technology, which locks organizations out of their own IT systems, has been used by a global network of hackers to inflict billions of dollars’ worth of damage to victims, through about $120 million in ransom payments and millions more in recovery costs, according to officials.

Five defendants have been charged in the US, officials said, including two Russian nationals. Two of the five are in custody. Another two alleged members of the gang were arrested in Ukraine and Poland on Tuesday, with law enforcement officials promising more to come.

“We will be closing in on those individuals,” said Biggar, adding that agencies had frozen about 200 cryptocurrency accounts and seized a “wealth of data” to fuel the investigation. “We’ve got a very clear understanding of the LockBit operation.”

That included seizing about 11,000 domains and servers around the world, as well as gaining access to nearly 1,000 potential decryption tools that could help more than 2,000 known victims regain access to their data.

Security researchers said earlier on Tuesday that LockBit’s website on hidden parts of the Internet—the dark web—had been taken down and replaced by a message stating it was “now under control of law enforcement.” Officials said the move was designed to humiliate and undermine the fearsome reputation of the group’s hackers, even as hundreds of its members, affiliates, and developers remained at large.

“There is a large concentration of these individuals in Russia,” said Biggar, who added that, while there was “clearly some tolerance of cyber criminality” there, the investigation had “not seen direct support from the Russian state.”

From its Russian roots, LockBit has collaborated with an international criminal syndicate through a so-called ransomware as a service model. The group rents out its malware to a loose network of hackers, who use it to paralyze a wide range of targets, from international finance groups and law firms to schools and medical facilities. LockBit typically takes a commission of as much as 20 percent of any ransom paid by victims.

LockBit’s attack in early 2023 on Royal Mail, the UK’s postal service, thrust the group into the spotlight, while its attack on the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the financial services arm of China’s largest bank, in November sent shockwaves through the financial world. That same month, gigabytes of data allegedly stolen from Boeing were leaked online after the aerospace group refused to pay a ransom.

The group has become so notorious that some hackers even got tattoos of its logo, part of a promotional stunt for which LockBit offered a $1,000 payment.

Chester Wisniewski, global field chief technology officer at cyber security company Sophos, said that LockBit, which is believed to have first emerged in 2019, had risen to become the “most prolific ransomware group” in the past two years.

“The frequency of their attacks, combined with having no limits to what type of infrastructure they cripple, has also made them the most destructive in recent years,” he said. “Anything that disrupts their operations and sows distrust amongst their affiliates and suppliers is a huge win for law enforcement.”

However, Wisniewski added that “much of their infrastructure is still online,” suggesting there was still work to do to bring the hackers under full control of law enforcement.

Additional reporting by Suzi Ring, Mehul Srivastava and John Paul Rathbone

© 2024 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.