Use of facial recognition software led Detroit police to falsely arrest 32-year-old Porcha Woodruff for robbery and carjacking, reports The New York Times. Eight months pregnant, she was detained for 11 hours, questioned, and had her iPhone seized for evidence before being released. It’s the latest in a string of false arrests due to use of facial-recognition technology, which many critics say is not reliable.

The mistake seems particularly notable because the surveillance footage used to falsely identify Woodruff did not show a pregnant woman, and Woodruff was very visibly pregnant at the time of her arrest.

The incident began with an automated facial recognition search by the Detroit Police Department. A man who was robbed reported the crime, and police used DataWorks Plus to run surveillance video footage against a database of criminal mug shots. Woodruff’s 2015 mug shot from a previous unrelated arrest was identified as a match. After that, the victim wrongly confirmed her identification from a photo lineup, leading to her arrest.

Woodruff was charged in court with robbery and carjacking before being released on a $100,000 personal bond. A month later, the charges against her were dismissed by the Wayne County prosecutor. Woodruff has filed a lawsuit for wrongful arrest against the city of Detroit, and Detroit’s police chief, James E. White, has stated that the allegations are concerning and that the matter is being taken seriously.

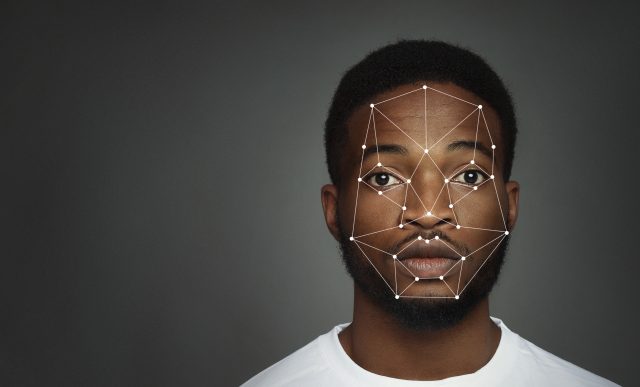

According to The New York Times, this incident is the sixth recent reported case where an individual was falsely accused as a result of facial recognition technology used by police, and the third to take place in Detroit. All six individuals falsely accused have been Black. The Detroit Police Department runs an average of 125 facial recognition searches per year, almost exclusively on Black men, according to data reviewed by The Times.

The city of Detroit currently faces three lawsuits related to wrongful arrests based on the use of facial recognition technology. Advocacy groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan, are calling for more evidence collection in cases involving automated face searches, as well as an end to practices that have led to false arrests.

“The reliability of face recognition… has not yet been established.”

Woodruff’s arrest, and the recent trend of false arrests, has sparked a new round in an ongoing debate about the reliability of facial recognition technology in criminal investigations. Critics say the trend highlights the weaknesses of facial recognition technology and the risks it poses to innocent people.

It’s particularly risky for dark-skinned people. A 2020 post on the Harvard University website by Alex Najibi details the pervasive racial discrimination within facial recognition technology, highlighting research that demonstrates significant problems with accurately identifying Black individuals.

A 2022 report from Georgetown Law on facial recognition use in law enforcement found that “despite 20 years of reliance on face recognition as a forensic investigative technique, the reliability of face recognition as it is typically used in criminal investigations has not yet been established.”

Further, a statement from Georgetown on its 2022 report said that as a biometric investigative tool, face recognition “may be particularly prone to errors arising from subjective human judgment, cognitive bias, low-quality or manipulated evidence, and under-performing technology” and that it “doesn’t work well enough to reliably serve the purposes for which law enforcement agencies themselves want to use it.”

The low accuracy of face recognition technology comes from multiple sources, including unproven algorithms, bias in training datasets, different photo angles, and low-quality images used to identify suspects. Also, facial structure isn’t as unique of an identifier that people think it is, especially when combined with other factors, like low-quality data.

This low accuracy rate seems even more troublesome when paired with a phenomenon called automation bias, which is the tendency to trust the decisions of machines, despite potential evidence to the contrary.

These issues have led some cities to ban its use, including San Francisco, Oakland, and Boston. Reuters reported in 2022, however, that some cities are beginning to rethink bans on face recognition as a crime-fighting tool amid “a surge in crime and increased lobbying from developers.”

As for Woodruff, her experience left her hospitalized for dehydration and deeply traumatized. Her attorney, Ivan L. Land, emphasized to The Times the need for police to conduct further investigation after a facial recognition hit, rather than relying solely on the technology. “It’s scary. I’m worried,” he said. “Someone always looks like someone else.”