For more than three decades, the Internet’s most key underpinning has posed privacy and security threats to the billion-plus people who use it every day. Now, Cloudflare, Apple, and content-delivery network Fastly have introduced a novel way to fix that using a technique that prevents service providers and network snoops from seeing the addresses end users visit or send email to.

Engineers from all three companies have devised Oblivious DNS, a major change to the current domain name system that translates human-friendly domain names into the IP addresses computers need to find other computers over the Internet. The companies are working with the Internet Engineering Task Force in hopes it will become an industry-wide standard. Abbreviated as ODoH, Oblivious DNS builds off a separate DNS improvement called DNS over HTTPS, which remains in the very early stages of adoption.

The way DNS works now

When someone visits arstechnica.com—or any other website, for that matter—their browser must first obtain the IP address used by the hosting server (which at the moment is 3.128.236.93 or 52.14.190.83). To do this, the browser contacts a DNS resolver that typically is operated by either the ISP or a service such as Google’s 8.8.8.8 or Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1. Since the beginning, however, DNS has suffered from two key weaknesses.

First, DNS queries and the responses they return have been unencrypted. That makes it possible for anyone in a position to view the connections to monitor which sites a user is visiting. Even worse, people with this capability may also be able to tamper with the responses so that the user goes to a site masquerading as arstechnica.com, rather than the one you’re reading now.

To fix this weakness, engineers at Cloudflare and elsewhere developed DNS over HTTPS, or DoH, and DNS over TLS, or DoT. Both protocols encrypt DNS lookups, making it impossible for people between the sender and receiver to view or tamper with the traffic. As promising as DoH and DoT are, many people remain skeptical of them, mainly because only a handful of providers offer it. Such a small pool leaves these providers in a position to log the Internet usage of potentially billions of people.

That brings us to the second major shortcoming of DNS. Even when DoH or DoT is in place, the encryption does nothing to prevent the DNS provider from seeing not only the lookup requests but also the IP address of the computer making them. That makes it possible for the provider to build comprehensive profiles of the people behind the addresses. As noted earlier, the privacy risk becomes greater still when DoH or DoT thins the number of providers to only a handful.

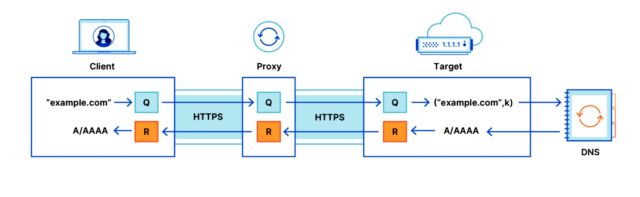

ODoH is intended to fix this second shortcoming. The emerging protocol uses encryption and places a network proxy between end users and a DoH server to guarantee that only the user has access to both the DNS request information and the IP address that sends and receives it. Cloudflare calls the end user the client and the DNS resolver operated by the ISP or other provider the target. Below is a diagram.

How it works

In a blog post introducing the Oblivious DoH, Cloudflare researchers Tanya Verma and Sudheesh Singanamalla wrote:

The whole process begins with clients that encrypt their query for the target using HPKE. Clients obtain the target’s public key via DNS, where it is bundled into a HTTPS resource record and protected by DNSSEC. When the TTL for this key expires, clients request a new copy of the key as needed (just as they would for an A/AAAA record when that record’s TTL expires). The usage of a target’s DNSSEC-validated public key guarantees that only the intended target can decrypt the query and encrypt a response (answer).

Clients transmit these encrypted queries to a proxy over an HTTPS connection. Upon receipt, the proxy forwards the query to the designated target. The target then decrypts the query, produces a response by sending the query to a recursive resolver such as 1.1.1.1, and then encrypts the response to the client. The encrypted query from the client contains encapsulated keying material from which targets derive the response encryption symmetric key.

This response is then sent back to the proxy, and then subsequently forwarded to the client. All communication is authenticated and confidential since these DNS messages are end-to-end encrypted, despite being transmitted over two separate HTTPS connections (client-proxy and proxy-target). The message that otherwise appears to the proxy as plaintext is actually an encrypted garble.

A work in progress

The post says that engineers are still measuring the performance cost of adding the proxy and encryption. Early results, however, appear promising. In one study, the additional overhead between a proxied DoH query/response and its ODoH counterpart was less than 1 millisecond at the 99th percentile. Cloudflare provides a much more detailed discussion of ODoH performance in its post.

So far, ODoH remains very much a work in progress. With shepherding from Cloudflare, contributions from Apple and Fastly—and interest from Firefox and others—ODoH is worth taking seriously. At the same time, the absence of Google, Microsoft, and other key players suggests it has a long way to go still.

What’s clear is that DNS remains glaringly weak. That one of the Internet’s most fundamental mechanisms, in 2020, isn’t universally encrypted is nothing short of crazy. Critics have resisted DoH and DoT out of concern that it trades privacy for security. If ODoH can convert the naysayers and doesn’t break the Internet in the process, it will be worth it.